On April 3, 1968, the enduring classic 2001: A Space Odyssey was released and now, fifty years later, film enthusiasts will have an extraordinary opportunity to see the picture in all of its brilliance.

Almost a year ago, filmmaker Christopher Nolan (Memento, Inception, Interstellar) released his war drama Dunkirk in 70mm around the country to critical acclaim and commercial success. It was around this time that he learned of a film reel of 2001 that had been made from the original camera negative but couldn’t be reprinted due to lack of funding. Nolan, empowered by the success of his 70mm screenings, went to Warner Bros. with his idea of making new prints of A Space Odyssey and releasing them, in the same way that Dunkirk was exhibited. This year at Cannes, Nolan debuted the new print of the film, which he makes clear is not a restoration — no digital work has been done — but rather a reprint created through an entirely photochemical process from reels that Warner Bros. developed in the late 90s.

Now, starting on July 6 at the Coral Gables Art Cinema, South Florida will have the opportunity to see 2001 as the audience members in 1968 would have seen it. The non-profit art house, which is the only theatre in the state of Florida with dedicated 70mm projection equipment, will have a week-long exhibition of what many consider one of the greatest and most influential films ever created.

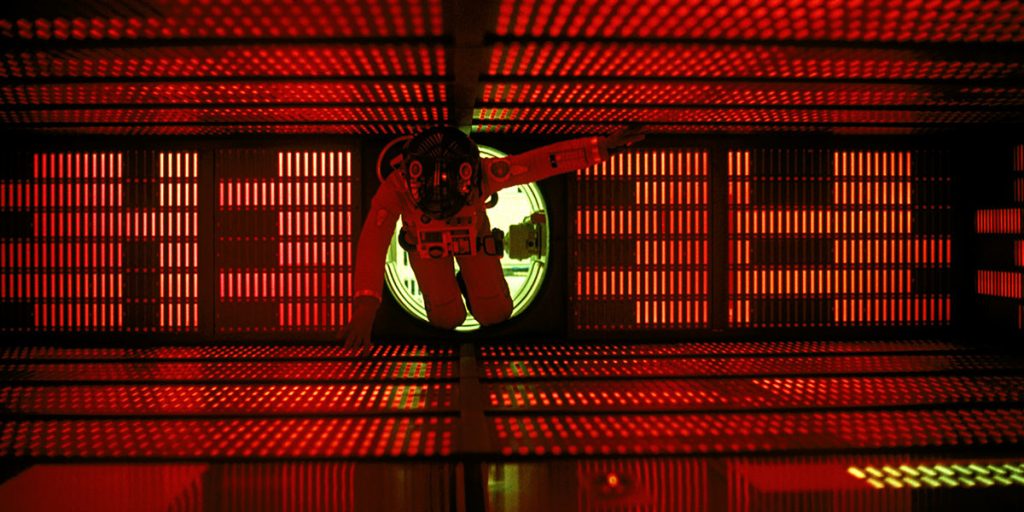

But why has 2001 lasted so long as not only the standard for science fiction films, but also for showcasing the transformative ability of cinema? Why are movie-goers of all ages passionately racing to get a look at this new print of a film that came out five decades ago? I’d argue that the film’s power lies in its ambiguity, its ability to be many different things to a diverse range of sensibilities. Kubrick, who co-wrote the film with esteemed science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, creates the film’s ambiguous nature by using strikingly little dialogue. Not a single word is spoken in the first twenty-five minutes of 2001, forcing us to interpret only with our eyes, and Kubrick understands how to shape and complicate subjectivity. The leisurely and deliberate shots of the film—all rich with elaborate special effects, costumes, and sets — allow for viewers to focus on different elements of the frame and truly form their own interpretations.

Depending on point of view, one viewer may see the film as ultimately having a positive outlook on the fate of the human race, while another person may read the ending as a grim evaluation of where we are headed as a species. Some viewers may be more interested in the ideas of consciousness and artificial intelligence as it relates to the supercomputer in the film, Hal 9000 (Douglas Rain). Others may see the film as a comment on the evolution of humans, or rather the illusion of progress. All that can be certain is that 2001 will continue to puzzle us, inspire us, scare us, and keep us coming back for repeated viewings.

Jose Ramirez is an English major minoring in Psychology and working towards a Film Studies Certificate.

Jose Ramirez is an English major minoring in Psychology and working towards a Film Studies Certificate.