Even if you don’t know who Marshall McLuhan was, you’ve probably heard the phrase “the medium is the message.” McLuhan was a Canadian philosopher whose theories about media were influential in 20th century thought and crucial for the development of media studies. But what did he mean by this cryptic phrase? There was a time in the 60’s and early 70’s when you would turn on the TV and see a whole table of people debating what McLuhan meant by a “cool” or “hot” medium, or the term “global village”, or entire phrases like “Heidegger surf-boards along on the electronic wave as triumphantly as Descartes rode the mechanical wave.” However, after fifty minutes or so it was decided that no one could understand what went through this man’s head and it was left at that. So, at the risk of becoming that one annoying media professor spitting gibberish behind Woody Allen’s ear in line for a movie theater, I will try to explain what McLuhan meant by “the medium is the message.”

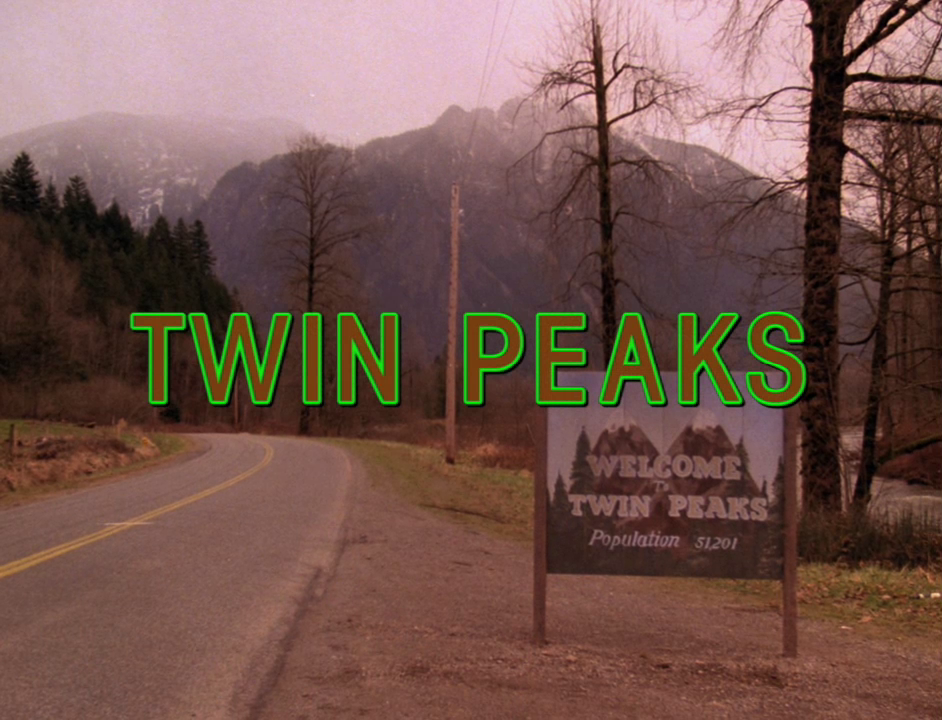

Simply put, McLuhan believed that the character of the medium is more important than its content. Since our attention is directed to the plot of a novel, the characters in a film, or the meaning of a song’s lyrics, we might not realize the full extent to which the media themselves (such as the printing press, the moving picture, or recorded music) govern our understanding of the world and alter social organization. By following the evolution of media, from pre-alphabetic to the electronic age, McLuhan proposes that media play a fundamental role in the ways that we experience and think about the world. Thus, the invention of the printing press and the mass production of books leads to a fragmentation of reality and television creates a “global village” of people all over the world tuning in to the same show to experience the same emotions and formulate the same ideas. A similar idea must have been floating in David Lynch’s mind when he created the revolutionary TV show Twin Peaks (1990).

Twin Peaks is quintessential TV – it is the complete deal condensed into neatly packaged one-hour episodes. It is romance, horror, comedy, thriller, teen drama, family drama, murder mystery, supernatural mystery, sitcom, cop show, spy show, and especially police procedural. It is a TV show that knows it is a TV show, an invitation to grab a TV meal and join others across America in the collective ritual that is watching a dream through a tube.

To add to this meta-narrative the show overexposes the face of the characters during critical scenes as if they themselves were watching TV, and has characters sporadically watch Invitation to Love, a parody of a soap opera/murder mystery that in turn makes us aware that what we are watching is just that. But the show goes a step further to establish itself as meta-TV by implementing through its symbology the harmful relationship between audience and producers as well as the material reality that makes TV possible in the first place.

This is quite the claim, so allow me to take a step back to discuss what I think David Lynch was trying to achieve with Twin Peaks. He was simply trying to bring balance to what he (rightfully) believed was a sick medium. The sickness was twofold – both the industry and its audience were sick. People wanted to see somebody being murdered and somebody else solving the whodunit in under an hour, and TV producers were more than glad to provide a weekly fix of easily forgettable cases to their junkie audiences. The cases were forgettable because the victims were forgettable – they were just a name and after a while less than that. Their names quickly faded into oblivion because their mystery was brought to a closure in the span of an episode of television. Death and violence then become nothing but a commodity for our entertainment and lose any other value they might have had if the producers had nobler aims in mind.

Here is where Twin Peaks departs the most from McLuhan’s materialist theories of media. While Lynch is aware that the form of the TV medium shapes the way we understand and organize the world, he goes a step further to place a moral significance on the content of the media we watch and make. There are other victims before Laura Palmer, and they are in fact named in the show, but they remain just that – names. Their names embody the sickness of TV, its weekly cheapening of death for our entertainment. But Laura Palmer has stayed with us all these years, and her name owes its transcendence to the fact that the mystery has remained open despite the audience and producers’ attempt to bring closure to Laura’s death.

Coming back to the point I was making before, there are many symbols within the world of Twin Peaks that help guide the viewer through Lynch’s ideas about the deplorable state of television. Fire is one such symbol. In Twin Peaks: The Return (2018), Deputy Hawk explains to the new detective in town (who in Lynch’s work is always the viewer) that the “fire symbol” is “a type of fire like modern day electricity” which is neither good nor bad in itself – its moral value “depends upon the intention behind the fire.” Fire can serve as a source of light, a guide through darkness, but can also destroy anything that comes into contact with its flames. That “electricity” which Hawk was referring to is the electricity that powers TV sets all around the world and thus is responsible for transmitting good or bad messages to the global village. Lynch was aware that the images being broadcast to our televisions were creating an atmosphere where fear and death are meaningless beyond our immediate entertainment. The fire was becoming uncontainable.

The child of fear and death, as episode eight of The Return makes clear, is Bob, the embodiment of evil in Twin Peaks. Bob, as the one-armed man says, “feeds on fears and pleasures” – he is a parasite that maintains a reciprocal relationship with the host. Like all the bad spirits of the “black lodge” – and like TV itself – Bob gives the people what they want to see: a corpse, a reason to keep engaged. The audience receives these images and by giving Bob their attention keeps the show running. Garmonbozia (or “pain and sorrow,” as the evil spirits call the disgusting gravy that they make from the corpses of their victims) comes to symbolize our hunger for on-screen violence and therefore what keeps the evil spirits alive inside the world of Twin Peaks – as well as in our own. We have an appetite for evil and the fire, the electricity in our living rooms, is more than glad to provide us with an unhealthy amount of it.

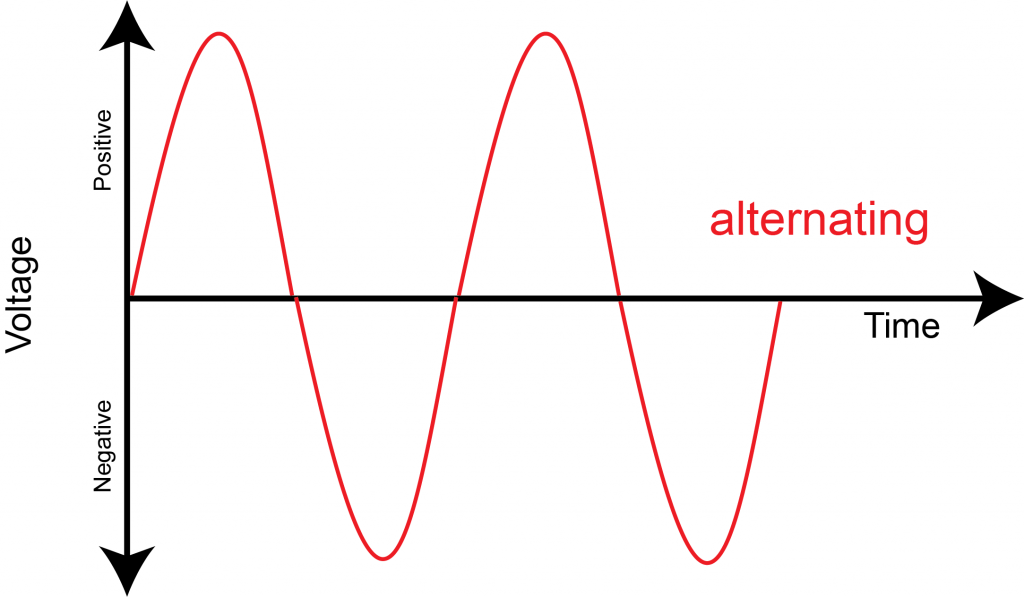

The genius behind Twin Peaks is that these symbols work not only in a metaphorical sense but are in fact intertwined with the material reality that makes television possible in the first place. The fire/electricity that powers our TV sets and makes the dream of television possible comes in the form of AC, or alternating current, which as the name suggests alternates between an equally positive and negative voltage. Each cycle or period of alternating current creates a positive and a negative peak, which represents the balance that Lynch was trying to bring back to television with his subtly titled show.

Some may wonder why, if Lynch was indeed trying to bring balance to TV, did he make a show filled with so much horrific violence and darkness? I believe that like Milton, Blake, and other great artists before him, Lynch understood the necessity of opposites: goodness does not exist in a vacuum, and virtue would not exist if one couldn’t choose to do evil. Lynch understood that one must know good by evil, and that only through this knowledge of both extremes can one begin to appreciate the good. In this sense, Laura Palmer is the embodiment of balance because she holds within herself both extremes of moral behavior. On the one hand she seems like a model daughter who gets good grades at school, tutors a mentally disabled kid, brings meals to and converses with lonely old people, and leads a healthy public life with her close circle of friends. On the other hand, agent Cooper’s investigation reveals that under the surface Laura was also dealing and consuming hard drugs, cheating on her boyfriend with multiple men, and prostituting herself at “The One-Eyed Jack.”

Laura’s complicated life, a life full of contradictions, full of light and darkness, is the perfect well from which an endless mystery can spring. But the irony is that she has to die to redeem TV. Lynch himself has to partake in evil before any goodness can be attained. And the audience, too, has a role to play in all of this – they have to watch the show. This is the big irony that Laura realizes – television lights flickering across her face – when the white angel comes to save her from the black lodge.

More than a decade after the airing of the first season, Twin Peaks remains an influential classic of television. It showed people that the medium can be something more than mindless entertainment, that like cinema (where Lynch places the good spirits of Twin Peaks), TV shows can tell us something profound about the human condition. But did it really bring about the balance that Lynch intended? I think that the answer is made clear in The Return: if anything, the world is even worse now. Crime and violence are more rampant than ever and the final redemption – the final perseverance of good over evil – is revealed to be a fake, ironic copy of a cheesy television ending that Cooper watches from inside the black lodge.

Joan Vega is an English major on the literature track in his final year of college. He spends his days reading modernist writers and listening to music. His favorite movie genres include horror and tragicomedy.

Joan Vega is an English major on the literature track in his final year of college. He spends his days reading modernist writers and listening to music. His favorite movie genres include horror and tragicomedy.